I was born in 1974 so my love of Stranger Things owes a lot to nostalgia. I catch every 80s reference that Stranger Things highlights. The boatload of 80s pop culture references get me in the door, but I stay because of the themes:

- As a parent, I resonant with the distinct theme of parents who resolutely go to hell and back to save their children. Well, OK, not hell; it’s the “Upside Down.”

- As a parent of a young teen (and having been one once myself), I totally get the characterization of young teens who are both immature and wise, typically at the same time.

- Friends don’t lie. I love how Stranger Things portray friendships so strong that it allows them to face literal monsters together.

- Finally, a middle school science teacher and select government agents are portrayed as the only folks in town who know the truth, which gives the whole show an aura of mystery. There are mysterious happenings going on just beyond what we, as the viewers, can see.

Now that I’ve led this horse to that last bullet point, we’ll now drink from the fire hose of unseen and malevolent forces that surround us. To do that, we first need to talk about an author named Frank Peretti. Please keep your hands inside the firetruck because this will be a wild ride.

The Satanic Panic

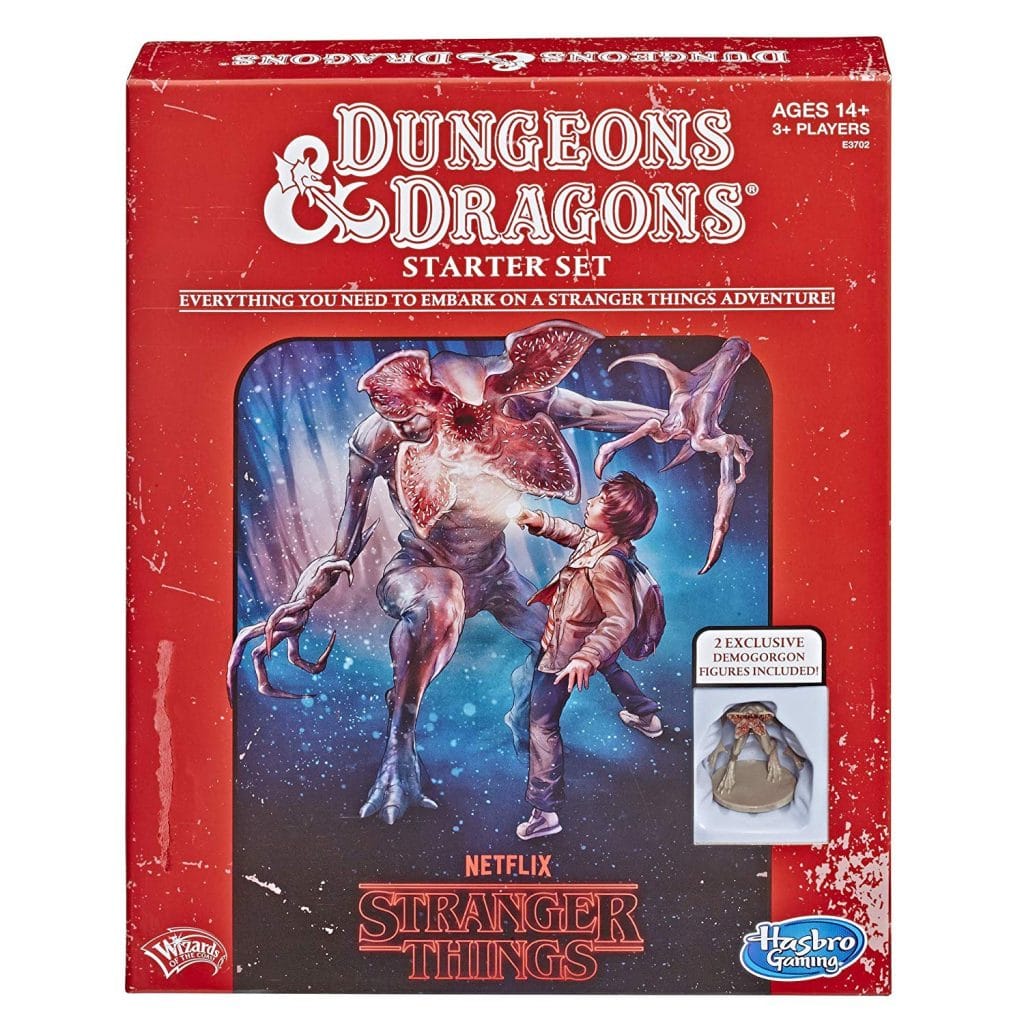

To understand Frank Peretti, we start by celebrating the idea that Stranger Things draws heavily from Dungeons and Dragons, right down to the specific monster choice. I love this fact because, despite my mother’s warnings, I was a total D&D nerd in the 80s.

Why was my mom so against D&D in the 80s and 90s? Well, maybe she was a secret government agent and had a real premonition about The Upside Down. More likely, however, is that she was simply swept up in the “Satanic Panic” of that time.

I’ve written more about the “Satanic Panic” if you want a deeper dive, but the summary is this: still reeling from the Jim Jones and Charles Manson cults of the 60s-70s and further frightened by the satanic writings of Anton LaVey, the American public in the 1980s had a distinct culture-wide anxiety surrounding child kidnappings and abuse.

The nightly news would breathlessly broadcast any troubled teenager’s runaway as certain evidence of foul play and the minds of the general public would immediate snap to the same conclusion: “Oh lord, those Satan worshippers must have kidnapped them!”

While I certainly don’t want to minimize or downplay the obvious horror of kidnapping and child endangerment or abuse, it’s obvious to say that the actual accounts of satanic ritual practices were much, much, much, much lower than the public believed. 99 times out of 100, the kids had simply run away to smoke weed with their ne’re-do-well friends behind the Knollwood Mall.

This cultural anxiety became known as the “Satanic Panic” and D&D became the primary scapegoat. An ill-informed public was looking for someone to blame and, since they didn’t understand the funny dice of D&D, they simply concluded that dice must be dangerous, satanic runes. Roll the bones? How frightening that children use actual bones as toys! It’s not possible.

As a result of this wild conclusion-jumping, the 2nd Edition of D&D removed the most obviously violent imagery of the game, like the Assassin class. Now, kids could only talk about launching magical missiles and lopping off vampire heads.

Frank Peretti’s Influence

What does this have to do with Frank Peretti? Well, the author wrote his two best-selling books in the 80s, obviously writing for an audience swept up in the Satantic Panic of the times.

One of the central conceits of Stranger Things is the existence of a plane of existence the boys call “The Upside Down,” a parallel dimension that exists alongside our own, but swaps out decay and death for every bit of life and flourishing on our own plane.

That is the exact same conceit of Peretti’s two most popular books, This Present Darkness (1986) and Piercing the Darkness (1989). Taking a very, very loose reading of Biblical texts, Peretti dialed up the cheese and drama surrounding demons and angels.

The plots of Peretti’s books blend monster horror, conspiracy theories, and innocents in fights for their lives, all wrapped in old-fashioned suspense. And writing in the 80s, the tropes of government conspiracies, single-parent families, rebellious teenagers, and casting a side-eye at the weird kid at school are in each Peretti book. You know, just like Stranger Things.

For our struggle is not against enemies of blood and flesh, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers of this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places.

Although written to be entirely fictional, Peretti was writing amidst the anxiety of the Satanic Panic where the public was looking for proof of dangerous and unseen forces surrounding them. The term “Upside Down” never appeared in a Peretti book, but darned if that exact imagery wasn’t spelled out on the page.

Audiences bought 15 million copies of Peretti books. And, oddly, sales were encouraged by Christian televangelists of the time. Televangelists deliver drama because it entertains. And Peretti’s imagery of demonic spiritual warfare was packed with drama. Peretti painted a vidid picture of “spiritual warfare,” an ancient combat between angels and demons that had now infiltrated America’s Heartland aka Hawkins, Indiana.

Peretti’s books excited imaginations to the point that some declared This Present Darkness as the best book ever written after the Bible and used it as a prayer manual. What does a declaration like that do? It elevates the work in the minds of the audience, giving a fictional account an unearned status to the point where many honestly started to believe it.

This is understandable and not that far-fetched. Over 80% of Americans believe in supernatural forces, although that number is much lower if you get specific on things like devil horns and pitchforks. Instead, most people believe that there very well may be a dimension beyond what we can see, an unexplained layer to reality that we can’t quite understand.

Peretti simply took those general, unspecific beliefs and added specific imagery. And it worked like a champ, especially because the “Satanic Panic” was worked into people’s consciousnesses anyway.

Was Peretti a true believer or a huckster? Was he looking simply to entertain and things spun out of control or was he in on it, intentionally stoking fears in order to drive sales? Did the devil make him do it?

We’ll never know and we don’t need to. We have in Stranger Things a wonderfully brilliant show that turns this idea of spiritual warfare upside down.

And how does Stranger Things begin? We meet the show’s children playing hours of D&D in their basement. Quite frankly, if we just had ten episodes of that, I’d be all in too.

Darned if that isn’t the exact thing the Stantic Panic warned us about.