In Joss Whedon’s Astonishing X-Men–which is being re-read for the thousandth time right now by many of the Nerds on Earth writing staff–he introduced a “mutant cure” sponsored by the warrior alien Ord. (The “mutant cure” plot was also the basis of the X-Men: The Last Stand movie plot, but the less said about that movie, the better.)

In Joss Whedon’s Astonishing X-Men–which is being re-read for the thousandth time right now by many of the Nerds on Earth writing staff–he introduced a “mutant cure” sponsored by the warrior alien Ord. (The “mutant cure” plot was also the basis of the X-Men: The Last Stand movie plot, but the less said about that movie, the better.)

The prospect of a mutant cure and having a “normal” humanity was immediately interesting to the furry Beast, who thought it might be nice not have to continue to cough up fur balls.

In fact, a mutant cure (reverting mutants back into ordinary humans) has long been a popular storyline in X-Men comics. But why in the 616 would any mutant choose the ordinary and normal, over the extraordinary and uncanny?

For real, what kind of person wouldn’t want to be a mutant? As a little kid I dreamed of having superpowers and it’s still fun to think about which superpower would be the best to have. To phase like Kitty, to teleport like Kurt, to control the weather like Storm…being a mutant would be a gift.

Who Wouldn’t Want to Be A Mutant?

The X-Men are in actuality mostly human as far as the full sequence of their DNA goes, although they refer to themselves as “mutants” and distinguish themselves from those they call “humans.” What’s interesting is that it is the normal humans who fear mutants. Instead of seeing mutants as a gift, they see them as something abnormal, something to be feared, ostracized, and punished even.

Right here is where I declare my bias: I’ve loved the X-Men since the 1980s spinner rack days. I love that the X-Men have long served as a metaphorical stand-in for the outcast and the excluded. When you are different, society will punish you to varying degrees. But pick an identity struggle, the X-Men teach us that our responses to that matter. Heroes like the X-Men are important for those who feel outcast, which is why it has been an enduring comic for decades.

But why do societies lash out against those they see as “other?” The prejudices toward mutants revolve around the idea of the “normal.” As a description, the word normal merely indicates something is statistically average, like normal 20/20 vision.

But is it true that just because something is normal, it should be our yardstick for how things should be? In other words, is “normal” something to be valued or something to be transcended? (Magneto would think the latter, obviously.)

There are limited ways to be normal: you must fall within a small range around the average score for various traits, whether physical, mental, or social. Again, think of a standardization like 20/20 vision.

But there are unlimited ways to be abnormal. Not only can you be an extreme in either direction from average (less “gifted” in an area or more “gifted”), but the way in which that extremity manifests can be wildly varied. In terms of our example, a lucky few are born gifted with 20/15 vision, whereas folks like me have 20/425 vision and wear glasses to adapt to that reality.

Whereas you might be talented, that talent could be specific to thousands of different areas! For example, it’s not normal how well Steph Curry shoots a basketball, which makes that ability to be very abnormal, far out of the range of the statistically average for that particular physical skill.

Whereas you might be talented, that talent could be specific to thousands of different areas! For example, it’s not normal how well Steph Curry shoots a basketball, which makes that ability to be very abnormal, far out of the range of the statistically average for that particular physical skill.

But there is a basic paradox of normality in the human species: we are social beings who feel a strong need to fit into a group (even “nonconformists” usually hang out with similar “nonconformists” – goths with goths, morlocks with morlocks, for example).

So there is a powerful innate and biological desire to fit within an acceptable range. Us humans don’t like to stand out.

On the other hand, we also want to attract attention to distinguish ourselves from others, so that we don’t get ignored. It’s a conundrum of the human condition: we want to fit in and we want to stand out.

Back to mutants and our question of who wouldn’t want to be a mutant. Beast and many other mutants are unable to pass as normal humans. This concept of passing (successfully pretending to be “normal”) is a well-documented real-life experience among homosexuals or maybe those with chronic illnesses that don’t change someone physically.

I have a very good friend who has Multiple Sclerosis (MS), a terrible disease. But her symptoms don’t manifest themselves physically as they might with many others who suffer from MS. She can pass as a normal, healthy adult. But while she could pass as “normal”, avoiding typical junior high persecution, others may not, like someone else with MS whose symptoms might force them to use crutches, for example.

Let’s pause for a second to make sure we’re being clear: abnormality is defined here descriptively, simply to mean statistically in the minority. “Abnormal” as a word isn’t used pejoratively here in any way, it’s being used to denote a minority symptom, trait, or orientation. The power of the X-Men as a metaphorical stand-in for the “abnormal” is part of the reason they’ve been enduring for decades.

Back to our story. The X-Men run the full spectrum:

- You could have an undetectable abnormality that causes distress when you attempt to hide it: say, a minority sexual orientation, social anxiety, Jean Grey’s unruly telepathy, or Rogue’s inability to touch.

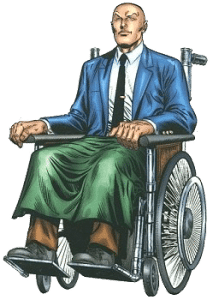

- You might even have a detrimental abnormality, such as Xavier’s paraplegia.

- One could have a hidden abnormality, such as a weak kidney, a photographic memory, or Kitty’s phasing.

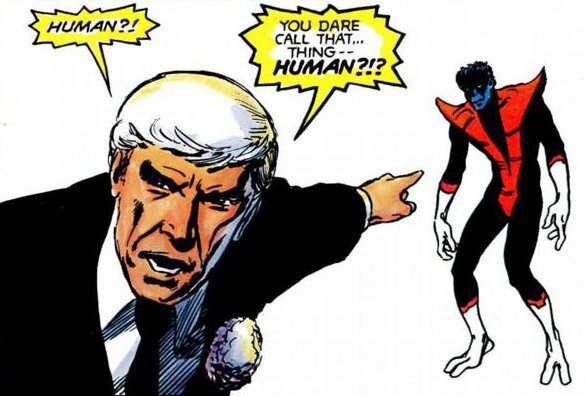

- Or you might have an abnormality that causes great emotional distress, such a missing limb, a facial deformity, or Nightcrawler’s appearance.

- Likewise, you might have a detectable abnormality that causes no distress, such as Colossus’ muscle-bound physique or Emma’s Frost’s beauty.

Each of the above examples are abnormalities that fall outside of what is statistically normal, but obviously, some are more socially accepted than others. Whereas some are shunned, others may be celebrated or affirmed.

It’s unfair, but once again, it’s a big reason that the X-Men have been such enduring characters of representation, beginning many decades ago when Charles Xavier became the first wheel chair bound superhero.

So who wouldn’t want to be a mutant? Well, the Morlocks have chosen to live underground–a realm that befits their rejection by both normal society and by mutants who can pass as normal. Some people may wish they had a Morlock’s powers, but few, if any, wish to look like a Morlock.

To empathize with a Morlock, it’s understandable that one wouldn’t want to be a certain kind of mutant–not the deformed or the weak or the kind of abnormal that interferes with living–while still loving the idea of being extraordinary in all of the beautiful and powerful ways one could imagine.

Science fiction, fantasy, and comic books provide an escape from the normal, allowing us to imagine the richness of a life that is enhanced by having special abilities and extraordinary experiences. We can dream of being a hero (even if we might not want to accept the responsibility of fighting evil every day!).

Who wouldn’t want to be a mutant? Well, people who are limited by their abnormalities and people who are ostracized because of their abnormalities, that’s who. But let’s remember that the X-Men have taught us that those are the very people who are always welcome on the team, accepted as family.

At their best, the X-Men have always flipped that script, fighting as heroes to teach society that the abnormal is beautiful, worthy, and valuable, and not to be feared, shunned, persecuted, or cured. That my fellow mutants, is why I’ll always love the X-Men.