If you can find a place in your heart, I urge you to spare a thought for poor Nathaniel Essex, a serious scientist who obsessively toiled to prove his theories, only to be shunned by the scientific community for his unorthodox experiments that many felt put him in unethical waters.

Later, a fateful meeting with Apocalypse granted Essex genetic knowledge from outside his own timeline. This, coupled with a transformation at Apocalypse’s hands, cast off his identity of Nathaniel Essex, making him the diabolical figure known as…

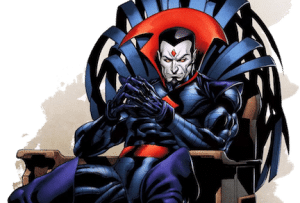

Mister Sinister!

Whereas heroic X-Men scientists such as Henry McCoy (Beast), Moira MacTaggert, and Charles Xavier (Professor X) were very often tormented by the moral weight of their choices, they are (mostly) able to resist the temptation to misuse their knowledge and power. But Mister Sinister rolled the other way.

Whereas heroic X-Men scientists such as Henry McCoy (Beast), Moira MacTaggert, and Charles Xavier (Professor X) were very often tormented by the moral weight of their choices, they are (mostly) able to resist the temptation to misuse their knowledge and power. But Mister Sinister rolled the other way.

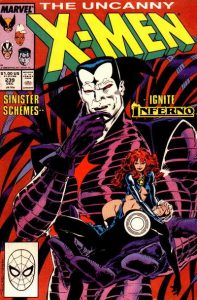

Sinister was a mad geneticist who would become one of the greatest foes the X-Men will ever face. And I just read The Further Adventures of Cyclops and Phoenix, which tells Mister Sinister’s origin story and I aim to tell you about it.

A comic which takes place in 1859, The Further Adventures of Cyclops and Phoenix features Nathaniel Essex / Mister Sinister, of course, but also features a historical Charles Darwin, something you don’t find every day.

Whereas the motives of Essex are at first noble and altruistic, his lack of a strong ethical foundation eventually allows him to tumble off the edge. He goes on to hire a band of thugs named the Marauders and begins to manipulating genes for his own selfish desires.

What is so Sinister About Genetic Manipulation?

But before we jump more into the story of Mister Sinister, let’s take a moment to talk about the scientific advances that happened in the decades that followed the nuclear bomb. Just like the X-Men, bioethics is a child of the atom that came of age in the 60s.

But before we jump more into the story of Mister Sinister, let’s take a moment to talk about the scientific advances that happened in the decades that followed the nuclear bomb. Just like the X-Men, bioethics is a child of the atom that came of age in the 60s.

Postwar scientists and physicians quietly began to step forward at a neck break pace, advancing much faster than a strong ethical framework could tamp down their worst impulses. There are historical cases of totalitarian regimes practicing unsupervised research on vulnerable populations, and even the United States has some skeletons in its closet when it comes to genetic experimentation over that time.

Bioethics is a field that rose up to help achieve balance between dangerous knowledge and power relative to a set of basic moral standards.

But let’s go back in time further still. Even before Charles Darwin’s work, Victorian England was seeing its society being shaken under social pressures. Victorians held their eyes high toward a loving God, yet were feeling doubts arise as they were confronted by Nature’s indifference to individual suffering.

Charles Darwin himself had been emotionally devastated by losing a child to disease. Likewise, the comic book origin of Nathaniel Essex was eerily similar, even as much as implying the loss to be a result of a rare genetic condition. They wondered, naturally, “what if science could save children like that?”

So as Charles Darwin and his fellow Victorians were having doubts about the basis of their moral convictions, the possibilities of using science as a weapon to rebel against the natural order, rather than meekly accepting it, were beginning to fill their thoughts.

Back to the comics. Upon becoming Mister Sinister, Essex exults at having “undergone what amounts to an industrial revolution of the mind,” shedding all moral restraint that he felt prevented him from reaching the highest summit of knowledge. Sounds relevant to Victorian England, eh?

Whereas most Victorians were still holding on to ideals of loving their neighbors and comforting them through tragedy, the ethics of some began to shift, thinking that real progress in science, economics, and politics was being thwarted by those compassionate thoughts. Mister Sinister sure thought so and he instead was a proponent of the intensely impersonal “dog eat dog”, “law of the jungle”, and “survival of the fittest” ethics.

But even the law of the jungle includes the need to support young offspring who cannot care for themselves! Indeed, even at it’s most dispassionate, ethics had been, and would continue to need to be, shaped by a natural balance between cooperation and competition, between aggressiveness and restraint. As usual, there was a need for heroes like the X-Men.

Egoists such as Mister Sinister (and Apocalypse and Magneto) consistently hail themselves as the next stage of evolution (agent’s of Nature’s will, no less) in eradicating those who stand in their way. (In the real world, we are haunted by examples of totalitarian villains have attempted similar rationalizations).

Yet a stronger case has always been made in support of the good guys like Moira MacTaggert, Colossus, Cyclops, and Jean Grey, whose “fitness” is reflected in their sacrificing themselves so that others may survive. Evolution may have a cruel side, yet those who confuse cruelty with genetic necessity are perhaps only making excuses.

For the X-Men the field of genetics hits close to home, which is why you’ll often find them fighting against those who would manipulate genetics in a sinister way, or against those who would discriminate against anyone who might be thought to have imperfect genetics.

But do benefits to our genetic future justify the breaking of a few embryos…er, eggs? Mister Sinister is equipped with comprehensive knowledge of molecular genetics and yet-undreamed future biotechnology, even if his methods have an old school Victorian flavor. Maybe the X-Men should just back off and let those like Mister Sinister play God with genetics?

But do benefits to our genetic future justify the breaking of a few embryos…er, eggs? Mister Sinister is equipped with comprehensive knowledge of molecular genetics and yet-undreamed future biotechnology, even if his methods have an old school Victorian flavor. Maybe the X-Men should just back off and let those like Mister Sinister play God with genetics?

Madeline Pryor was a genetic creation of Mister Sinister. And Madelyne Pryor was the genetic clone of Jean Grey, even as far as being implanted with her memories. Yet Sinister was confounded when Madelyne Pryor nevertheless fails to manifest power’s like Jean’s. Could it be that greatness is more than the sum of our genetic parts?

Well, his name is Sinister, after all. We’d all do well to remember that maybe the power of total control over other’s genetics can lead to corruption if there isn’t a strong foundation of bioethics to hold those impulses in check.

Oh, but it’s just a comic book, you are probably saying. What could a comic possibly have to teach us in the real world?