JRR Tolkien’s influence is pretty much in every nook and cranny of the fantasy genre. As you round the corner into Fantasyville, you come face-to-face with Tolkien and you have to quickly apologize for almost walking into him. When you lift up the couch cushion in fantasy’s living room, you find Tolkien there, wondering why it took you so long to discover him. Tolkien dated your fantasy sister one Summer; he’s everywhere.

Tolkien’s influence on the fantasy genre can’t be overstated. But did you know that Tolkien also unwittingly influenced the alignment system of D&D? I’ll explain via a few vignettes that will come into “alignment” by the end of the article.

Tolkien and the Good – Evil Axis

JRR Tolkien and CS Lewis were buds and both of their extensive writings framed reality in terms of good and evil. No one would question the depth of Tolkien’s work and few would question the hopefulness in his writings either. Although Tolkien’s characters have long journeys to traverse, there was no question that goodness would prevail, no matter how small its vessel. In fact, there is a term for the hopeful optimism of Tolkien: Eucatastrophe.

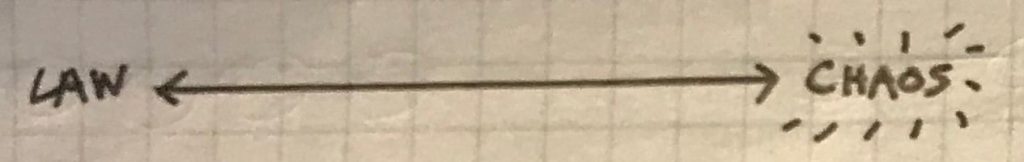

Tolkien influenced others in this matter. In the same timeframe of Tolkien’s writings, Poul Anderson released Three Hearts and Three Lions. Otherwise unremarkable, Anderson’s fantasy novel has the same dualistic nature of good and evil as Tolkien’s. The book attempted to make sense of World War II by using a parallel fantasy world as an allegory, representing the war as a battle of the great forces of Chaos vs. Law.

The heroes joined the forces of Law who were lead by the Roman Catholic Church, while the forces of Chaos were driven by witches, trolls, and fairies. Three Hearts and Three Lions was a major influence on D&D, with many of the monsters appearing as key characters in D&D co-creator Dave Arneson’s Blackmoor campaign setting. That’s OG D&D.

Moorcock and the Lawful – Chaotic Axis

A decade later, a writer named Michael Moorcock used Three Hearts and Three Lions as the basic framework for a series of novels he wrote. The difference was that Moorcock took that Law / Chaos continuity and turned it on its side.

Moorcock was going through a difficult period in his life, was disaffected, flat broke, drinking heavily, and had just been dumped by his girlfriend. In other words, he was a far cry from the pious and steadfastly faithful Tolkien.

Unlike Tolkien, Moorcock was morally uncertain and had grave doubts about humanity. So Moorcock took this same idea of duality, but had it represent his own sense of alienation. The structure of the books were nods also to Robert E. Howard‘s Conan the Barbarian series, yet Moorcock’s novels featured heroes that were anything but.

Whereas Conan was physical perfection, Moorcock wrote anti-heroes that relied on drugs to provide their strength. Moorcock’s anti-heroes would make bargains with devils and became corrupted in the presence of powerful artifacts. Put a pin in this as we transition to Chainmail.

Chainmail Sets The Stage

Forming the foundation of D&D was Chainmail, a set of wargaming rules that took mass combat and focused them on a single hero. Designed by Gary Gygax, Chainmail was free-wheeling and loosy-goosy, but it introduced many of the features of D&D, including the concept of alignment.

And Chainmail explicitly referenced both Tolkien contemporary Poul Anderson as well as Michael Moorcock.

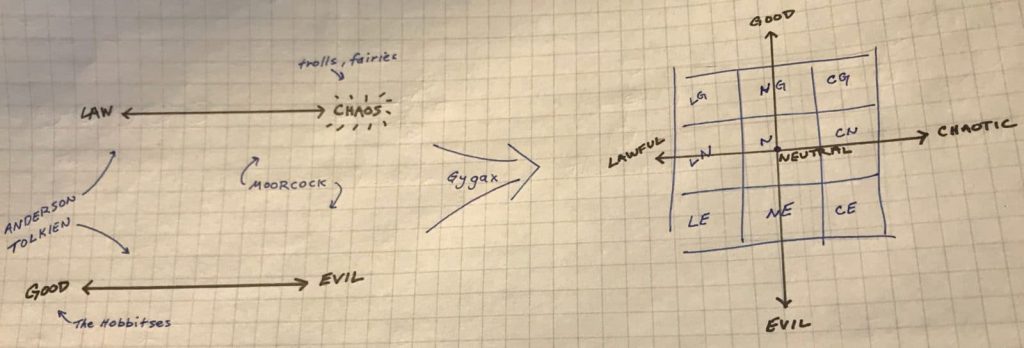

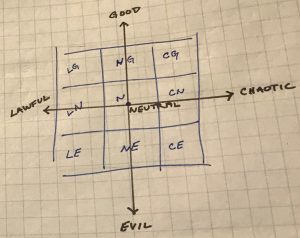

The D&D alignment system was designed to incorporate the dualism of Tolkien that featured a moral and religious certainty, as well as the dualism of Moorcock, which was an existential malaise. This is where we got both the Law – Chaos axis as well as the Good – Evil axis. When this is gridded out, we get D&D’s nine alignments.

D&D Alignment

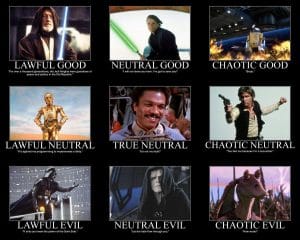

Few other RPGs frame alignment in as stark and delineated term as D&D, but the genesis of the system is the deep influence of fantasy giants like JRR Tolkien and the religious faith of Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, D&D’s creators. Forty years later and the alignment system continues to influence culture, now mostly popping up in meme generators that quiz us to pinpoint our personal alignment.

Alignment is hanging by a thread though, as the decades since have brought a few “competent men” writers such as Robert Heinlien who would lean towards Tolkien but those same decades have brought hundreds more like Frank Miller, Alan Moore, and others who have deepened the anti-hero outlook. Now most gamers scoff at humans having an essential moral nature than can be plotted on a couple axis.

But alignment is just a theoretical model or morality, after all. It is only intended to help order the game. Indeed, its usefulness is in its consistency not its realism. And D&D doesn’t guarantee that the good guys will win in the end. A TPK might befall your lawful good paladin, just as it might a chaotic evil rogue.

But alignment is just a theoretical model or morality, after all. It is only intended to help order the game. Indeed, its usefulness is in its consistency not its realism. And D&D doesn’t guarantee that the good guys will win in the end. A TPK might befall your lawful good paladin, just as it might a chaotic evil rogue.

But interesting to note, when the game was studied, the researcher found that 80% of players chose to play “good” or “lawful” characters and this was highlighted by Religious Studies professor Jospeh Laycock, the author of Dangerous Games, the Bible on D&D and morality. Perhaps that’s because characters that are cooperative and trustworthy often succeed in the game, whereas selfish characters often do not.

Huh. So maybe there is something to a moral compass after all. Maybe that can give us some hope and encouragement beyond our characters and into the real world.