I was a teen in the 80’s. It was a time that really helped forge my identity as a nerd forever. I remember Empire Strikes Back, E.T., Goonies, Commodore 64, and riding bikes with my friends to the Putt-Putt just a few miles from our neighborhood where they had a KILLER collection of arcade games.

There’s been lots of nostalgia stirred up recently with reboots of movies and tv shows, the arrival of Stranger Things on Netflix, and even games like Kids on Bikes (check out fellow nerd Brandon Morgan’s excellent review) and GasLands (a Car Wars type game also reviewed by Brandon).

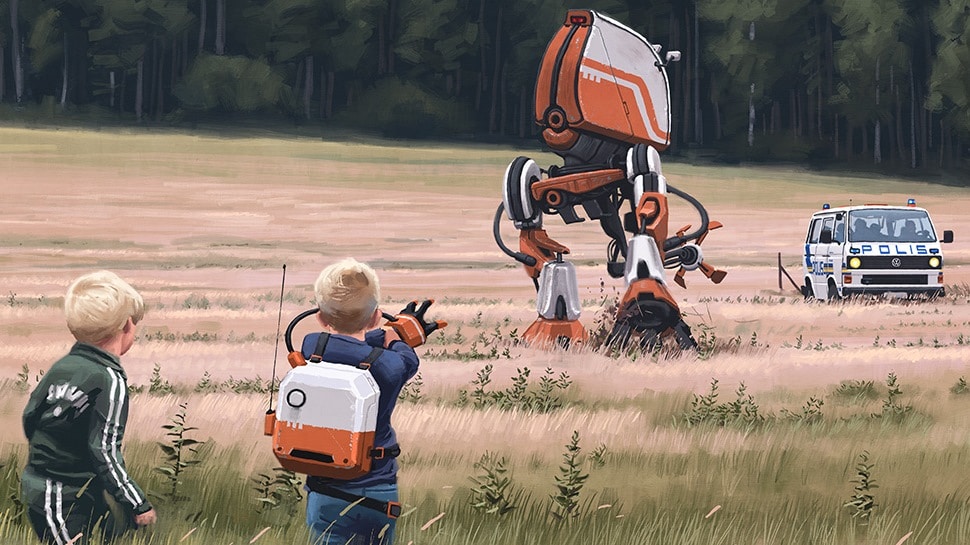

Tales from the Loop is another RPG that scratches that same 80’s nostalgia itch. It was inspired by Simon Stålenhag who published a book of his captivating artwork and stories that blend simple rural and urban scenes from the 80’s and 90’s [“Cool!”] with futuristic machines and vehicles [“Yeah?!”], Robots [“Awesome!!”], and DINOSAURS! [“AAIIIEEEE!!!”]

Excuse me, I’m going to need a moment…

Thanks. Now, where was I? Oh yeah, the game…

Back to the Future: An overview of Tales from the Loop

The core Tales from the Loop book is gorgeous! The design is crisp, clean, and engaging with its bright colors and the inclusion of lots of Stålenhag’s beautiful illustrations. It’s a solid book weighing in at 191 pages, and it includes everything you need to get playing.

It all starts with a quick intro for people who may be new to RPGs. There’s a brief description of the setting, a quick example of game play, and then an explanation of how RPGs work. Then, it gives a concise list of the principles of the game (I love nice little nuggets like this because they’re easy to understand and remember) that include things like “your home town is full of strange and fantastic things”, “adults are out of reach and out of touch”, and “the world is described collaboratively”.

The book dedicates two chapters to describing the settings: one in Sweden (Stålenhag’s home), and one in the US; and each have some beautiful supporting maps. Of course, the descriptions of locations and the technology of the world make it easy enough for the GM to adapt the game to any setting, you’d just miss out on the maps.

Creating characters is a pretty straightforward process. Like the things that inspired this game (and Kids on Bikes), the characters in this game are kids. Unlike Kids on Bikes, this game takes a shorter view of a character’s career. In Tales, a character is between 10 and 15 years old (when a character turns 16, they are “no longer considered a kid for the purposes of this game”).

Age does affect the game, in that you have a number of skill points to allocate based on your age. The older you are, the more points you get to allocate to your base attributes. Conversely, the younger you are, the more points of “luck” you have (luck allows you to reroll dice). The results are older kids are better with certain skills (more dice in their dice pool for those skills), but younger kids are more versatile (luck can be spent to re-roll any skill).

Age does affect the game, in that you have a number of skill points to allocate based on your age. The older you are, the more points you get to allocate to your base attributes. Conversely, the younger you are, the more points of “luck” you have (luck allows you to reroll dice). The results are older kids are better with certain skills (more dice in their dice pool for those skills), but younger kids are more versatile (luck can be spent to re-roll any skill).

A character’s base attributes are body (similar to strength and dexterity), tech (intelligence/wisdom-ish – related to physical things, like machines, computers, and locks), heart (charisma), and mind (intelligence/wisdom-ish – related to people, creatures, riddles, etc.). Each attribute will have a score between 1 and 5. A character has a number of points equal to their age. The remaining points (15 – character age) are luck points.

As your character ages, you lose luck points as they are transferred into attribute points. A character also has some skills that can be improved through experience points. There are standard archetypes provided to help you build your character, including computer geek, jock, and popular kid.

These archetypes give you direction for other character aspects: skills, problems, drives, prides, relationships, and anchors. Those aspects are useful in driving the narrative. The anchor is interesting in that it is the person that helps a character when they are hurt. In Tales from the Loop kids can’t die, but they can get hurt (acquire a condition). When they’re hurt, they need to interact with their anchor to remove conditions.

Possible conditions are upset, scared, exhausted, injured, and broken. These conditions are results of skill checks (rolling dice).

The mechanics of the game are based on the Year Zero Engine. When facing trouble, a player will build a dice pool where the number of dice is determined by the adding the value of the relevant attribute and relevant skill. You may have an item that gives you a bonus or a condition that give you a penalty. A result of a 6 on a die is considered a success. You may need 1, 2, or 3 successes to overcome trouble.

Spending a luck point, or pushing yourself will let you re-roll. If you get more successes than needed, you get to choose from a list of bonuses for each skill which include not having to roll in a similar situation in the future, or being able to give another character a bonus die for a future roll.

Failure however, as well as pushing yourself, result in acquiring a condition (-1 to your dice pool). To heal or remove a condition, a character must spend time (play out a scene) with their anchor where they talk through the problem. As a counselor who uses games to promote growth and development, I love this mechanic. It’s a great way to play out real life struggles in a safe way.

The rest of the book includes a year long (game time) campaign that can be played in either setting – with supporting maps and artwork. There is an additional book available that includes mysteries to solve, new machines, and more information for game masters to create their own mysteries and campaigns. You can also get custom dice, a GM screen, and beautiful printed maps from your FLGS, publisher Modiphius, or however you reach you’re favorite gaming vendor.

Oh yeah, Stålenhag’s work has recently been picked up by Amazon for a new show on Prime.