When I saw Deadpool, I received a little bit a ridicule for furiously scrawling in my notebook during the trailers. I’m not saying I didn’t deserve it, but I do think it was worth doing, as the thoughts I was recording seemed then, as now, somewhat profound.

I was making notes about the content of the trailers, which, if my notes are correct, included X-Men: Apocalypse, Batman v Superman, Captain America: Civil War, and Purge: Election Year. All four of those movies have a common thread, which is the implied or explicit collapse of civilization. It’s not even subtle, not when you’ve got movies where the good guys actually fight people called “Doomsday” and “Apocalypse.”

It’s not just those; there was Mad Max and San Andreas last year, and a new Independence Day now. Walking Dead is still is a major force on TV. There was something called the Fifth Wave that completely escaped my awareness, but I have a dim notion that it exists.

I don’t think it’s very surprising that our popular consciousness has taken a turn for the apocalyptic. We’re grappling with terrorism, financial crises, political unrest, and climate change leading to droughts in California, wildfires in Canada, and flooding in West Virginia. The European Union is splintering; the Olympics are threatening to unleash a plague across the world; Venezuela has joined Greece and all the other nations that are too poor to afford cracked earth. These are uncertain times, and now, as ever, our art reflects our mood.

What I find far more interesting (in the same way an epidemiologist finds a new strain of bacteria-resistant superflu interesting), is a less common narrative thread that shows up in at least four otherwise very different works:

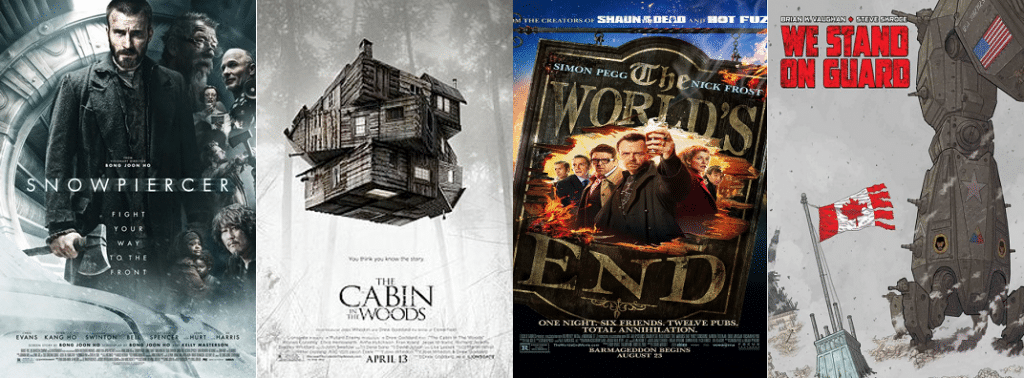

- the class-struggle-on-a-train thriller Snowpiercer,

- the over-the-top science-fiction comedy The World’s End,

- loving horror pastiche Cabin in the Woods,

- and Brian K. Vaughan’s remarkably unsubtle Iraq War allegory We Stand On Guard.

I’m going to start talking about the endings of those movies in about eight words or so. Consider this your spoiler warning.

- In Snowpiercer, reluctant revolutionary leader

Steve RogersCurtis confronts Wilford, the conductor of the train into which the entirety of the Earth’s population is crammed. Wilford makes Curtis an offer: assume control of the train. He can keep the population safe, stable, and alive. - In Cabin in the Woods, college student Dana is told that she can prevent the destruction of the Earth at the hands of the Old Gods.

- In The World’s End, lovable goofball (and severe alcoholic) Gary King can keep the world’s technology running smoothly.

- In We Stand On Guard, Amber learns that her crusade is (potentially) misguided, and that if she stands down, she will ensure that the United States will continue to have access to clean water (that’s kinda reductive, but I don’t have time to get into it right now).

Thus, we see the common theme: the main characters have a choice, and there’s a price that has to be paid. In Snowpiercer, it’s maimed children; in Cabin in the Woods, it’s the life of a friend; in The World’s End, it’s individuality; and in We Stand On Guard, it’s collaboration with an invading force. It’s a difficult choice, of course, but one familiar to anyone who has seen Wrath of Kahn; the lives of the many, etc.

And yet, what happens? The train is explosively derailed. The Old Gods ravage the world. The alien overlords leave the Earth in the Dark Ages. And Amber detonates her bomb vest and poisons the entire East Coast.

The conclusion here is inescapable, and that is that in each case, the world is built on a fundamentally toxic foundation. There can be no fruit from a poisoned tree. The characters are presented with the opportunity to preserve this system for the greater good, and yet they all decide that it would be better if the entire thing was destroyed, regardless of who it would hurt. It would be better to die than to live another second as part of a system that would extract so high a cost, even if it is only a single person.

If any of that rhetoric sounds familiar to you, it’s because for the past six months, Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders have been saying almost the exact thing to fuel their efforts to be President of the United States. The system is broken. It’s corrupt. It’s rigged. It would be better to tear it up than compromise, even if the result is total destruction.

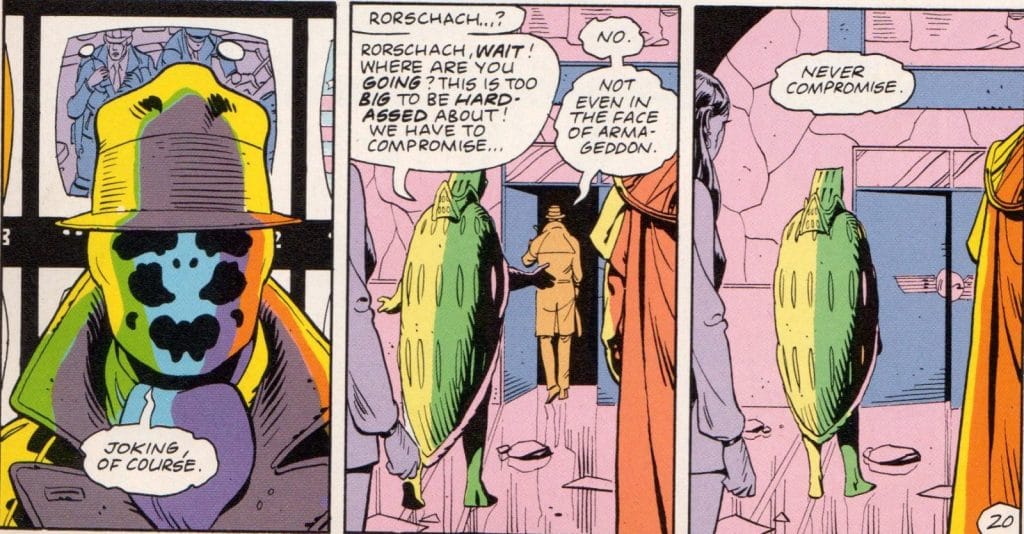

Wait a second. Where have we heard that before?

That’s right, Rorscach, the infamously uncompromising vigilante from Watchmen, the guy who was so outrageously inflexible that Alan Moore actually meant for him to be a parody of Steve Ditko’s Mister A and the Question.

Four data points are not enough to indicate a trend, of course. The vast majority of entries into the canon of popular culture show the good guys triumphing over incredible, seemingly insurmountable odds. The rift between Captain America and Iron Man is repaired; Doomsday is forestalled; the Apocalypse is…oh man, what’s the word?

But. But there’s still something, something that’s digging into our minds, some notion that we just can’t let go, isn’t there? We’re all looking around at this world, and are we wondering that maybe, just maybe, this isn’t a place worth saving? Maybe we’re becoming aware of the weight of all of our sins, and we’re deciding that we haven’t done so hot of a job after all?

Madness, of course. There is hope, always. But now, as ever, art reflects our mood.

So with art like this, what kind of mood must we be in?