Ugh. 2019. Am I right? I’m not sure about anyone else, but the news cycle of late has really gotten me down. There are too many divisions in our society and too few areas of consensus. As I write this, the government shutdown chugs along at the slothful pace of a lumbering beast, unwieldy and cumbersome. Turn left or right and we’re constantly assaulted by divisiveness. I need some balance. I need a break.

We here at Nerds on Earth try not to get too political when it comes to our passions. That can sometimes be a tricky tightrope to walk. We all have our own unique preferences and bias towards our choices in nerdy entertainment. Especially when it comes to comic books, there’s a clear tendency to support Marvel amongst the denizens of the Halls of Nerds on Earth. I’m an avowed Marvel Zombie, but we nerds don’t have to settle for bickering and rancorous acrimony between the Big Two.

Despite their differences, common ground can be found between DC and Marvel. Like a fine wine paired with the right cheese, having a balanced diet of comic books from Marvel and DC can bring a sense of fulfillment and satisfaction when mated with a suitable companion from across the aisle. So, in the spirit of bipartisanship, I want to offer some harmonious couplings of classic tales to bring our reading experiences into peaceful balance.

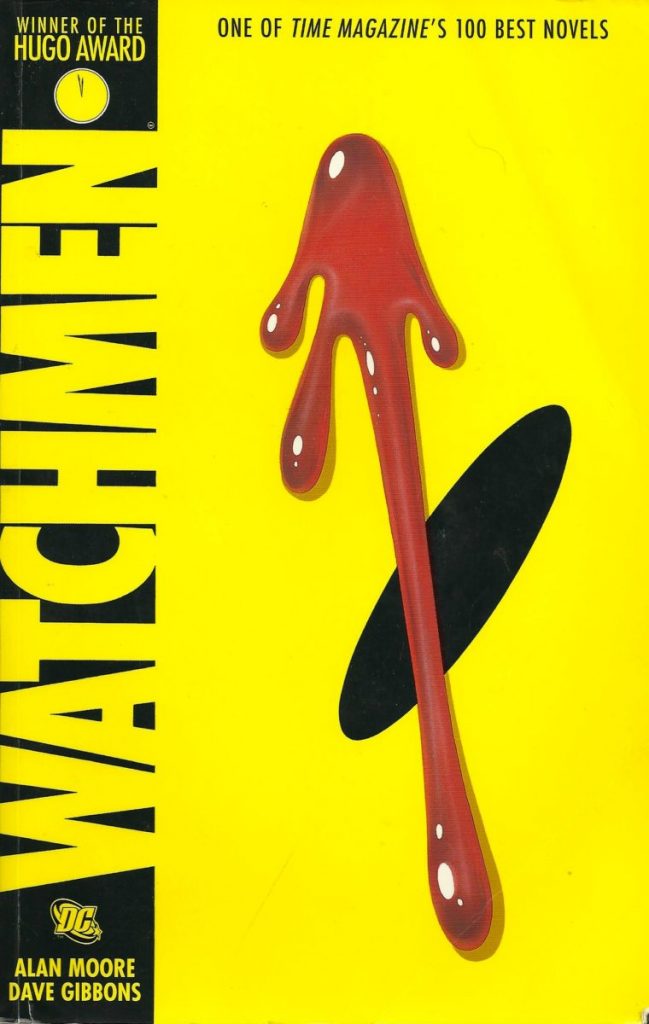

Watchmen & Squadron Supreme

Let’s start our perfect pairings by examining the superhero genre itself. While navel gazing and deconstructing the superhero genre is old hat in today’s world, both Marvel and DC did it first in the mid-1980s. Creators like Frank Miller, Alan Moore, and Howard Chaykin are often credited with breaking the norms of the previous generation by looking inward at the superhero. Both Watchmen and Squadron Supreme did this by deconstructing the superhero myth in very similar ways.

Widely considered by many to be the greatest comic book story of all time, Watchmen has certainly earned its reverential spot in history. The legendary twelve-issue series from Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, and John Higgins has influenced a generation of comic books. If anything from the medium is required reading, it’s Watchmen. Fairly or not, Watchmen is the standard by which all modern comics are judged. The story’s potency is due in large part to its exploration and deconstruction of the superhero genre itself. Watchmen isn’t a feel-good story. It tells the story of a world on the brink of nuclear destruction and the banned superheroes who are trying to deal with the chaos. The interpersonal drama between the former members of the Watchmen plays out like a Shakespearean tragedy. In the end, the heroes aren’t necessarily heroes any more, but byproducts of a broken system.

Often overshadowed by the Watchmen juggernaut is Marvel’s Squadron Supreme miniseries from 1985, a year before Watchmen hit the stands. While Watchmen is familiar with many comic book fans, many people tend to forget the landmark storytelling of Squadron Supreme. Mark Gruenwald’s classic deals with very similar themes to Watchmen. Lured by the beliefs that their superpowers make them the obvious choice to recreate the world into a utopia, Squadron leader Hyperion leads an effort to replace the government of the United States and rule in its stead. If great power comes with great responsibility, it must also come with great consequence and suffering. The Squadron’s behavior modification program comes with interesting abuses of power on the art of its members. Squadron member Nighthawk tries to remedy the situation, leading to a violent confrontation that has Squadron questioning their motivations. I would argue that Squadron Supreme stands out, like Watchmen, as Marvel’s magnum opus on the superhero genre.

Man of Steel & Ultimate Spider-Man

One of the great tropes of superhero comics is the reinvention or reinterpretation of longstanding characters via the reboot. Afterall, some of these characters have been around 80 years. Even with characters that have been around only a fraction of that time can find themselves buried in weighty continuity. The reboot can provide a way to honor what has come before, while giving the new creative team (or teams) a chance to leave their own mark on a title without having to make sure they don’t contradict something from a story released 42 years earlier.

John Byrne’s post-Crisis reboot of Superman in the Man of Steel miniseries is considered by many to be the standard bearer for such reimaginations. The six-issue miniseries follows a modern-day reimagining of Superman’s origin, meant to give readers a way to update and refresh the Superman legend after the entire universe reset button had been pressed with 1985’s Crisis on Infinite Earths miniseries. Man of Steel gave a fresh coat of paint to the superhero who was first introduced in the late 1930s. It also served as a way to reintroduce readers to Superman’s supporting cast, and importantly changed Lex Luthor from being a mad scientist into a ruthless businessman and industrialist we all know and love today. Superman’s origin has seemingly been retold a few thousand times since then, but all the subsequent reconfigurations of Superman’s origin borrow heavily from Byrne’s reimagination set forth in Man of Steel.

Though not as succinct as Man of Steel, Ultimate Spider-Man served as way to refresh the concept of everyone’s favorite web slinger. Ultimate Spider-Man debuted in late-2000 and ran for over 200 issues, and in many ways is still going if one counts the current Miles Morales book as a continuation of the Ultimate Universe line. The purpose of the Ultimate Universe was to update the old stories from the original Marvel Universe to the 21st Century without having to do a line-wide Crisis style event at Marvel. Brian Michael Bendis and Mark Bagley had an instant hit on their hands reworking the Spider-Man mythos. Throughout its original 133 issue run, Ultimate Spider-Man gave readers an update that wasn’t steeped in dark, gritty, and jaded reimagining of all our favorite Marvel heroes (they left that to Mark Millar’s Ultimates). What Ultimate Spider-Man did give us was a fun, rich comic book that often outsold and out-told Amazing Spider-Man for years. It was appointment level reading in a way that Spider-Man hadn’t felt like in more than a decade. Ironically, Bendis has moved on to DC to tackle Superman, which all began with yet another reimaging miniseries titled, you guessed it, Man of Steel.

Kingdom Come & Marvels

Sometimes comic books are connected by more than just thematic elements. Alex Ross provides our next two books with its connective glue that make for a good reading pairing. Ross’s lush painting style immediately adds gravitas to almost any project he is associated with. It doesn’t hurt that he’s collaborated with some of the best comic book writers of the day.

In 1996, Ross collaborated with Mark Waid on DC’s Kingdom Come miniseries. Kingdom Come stands out as yet another example of deconstructing the superhero genre, which by 1996 had become a rather crowded field. However, Kingdom Come takes a refreshing look at the genre, pitting the traditionalist ideas of older heroes up against the angsty, extreme (X-TREME!!!) vigilante of the 1990s. The Elseworlds story follows the everyman narrator Norman McCay as he witnesses a unraveling superhuman war that poses a very real threat to all life on Earth. In the middle, we find Batman and his team of heroes who are attempting to avoid the apocalypse. As with all Elseworlds tales, it remains out of continuity, but not out of relevance. The idea that heroes should be ambassadors more that fisticuff vigilantes is a strong one that can be seen in Waid’s other works. It seems that the new Good Guys aren’t much better than the Bad Guys. Kingdom Come was followed up by a sequel/prequel called The Kingdom, but Ross left the project over creative differences.

Two years earlier, Ross had collaborated with Kurt Busiek on the Marvels miniseries. Like Kingdom Come, Marvels is narrated by an everyman, this time by Daily Bugle report Phil Sheldon. Marvels focused on how everyday folks would live and cope with a world full of, you guessed it, Marvels! Unlike Kingdom Come, Marvels focuses on the past rather than the future. Set between the late 1930s and the 1970s, Marvels zeroes in on putting your faith in heroes. Marvels isn’t so much a deconstruction of the superhero genre as it as celebration of what life truly means, the beauty and tragedy of it all. Like Kingdom Come, a couple of sequels were released thereafter to varying degrees of success and without Ross as the primary artist. Regardless, Ross elevates already strong stories in both series, proving that the 1990s weren’t just about pouches, ridiculously large guns, more pouches, muscles, and cleavage!

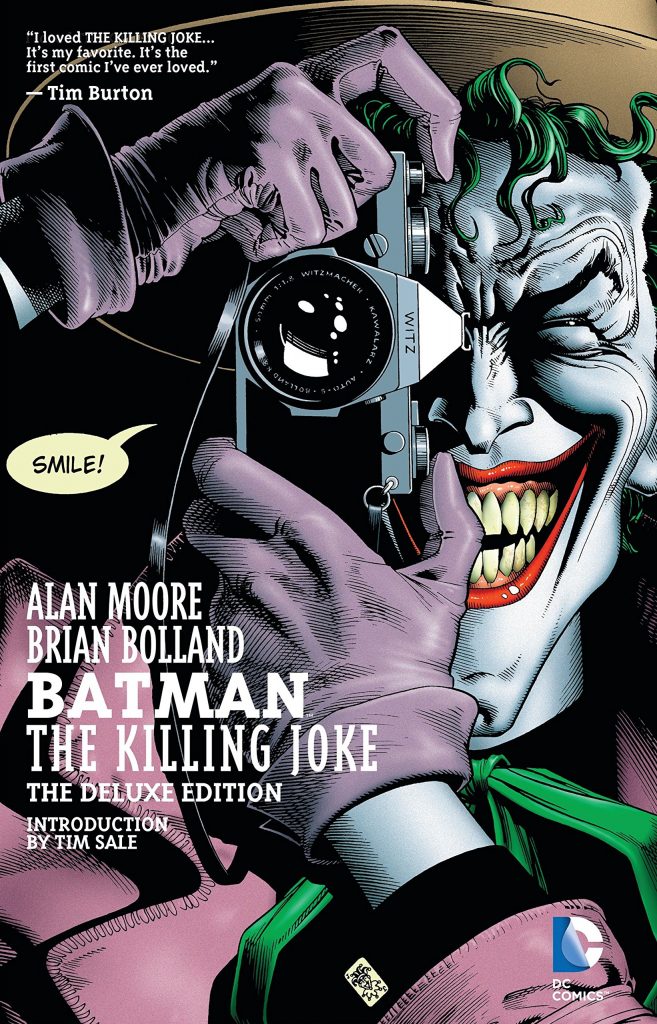

Killing Joke & Kraven’s Last Hunt

Comic companies, especially Marvel and DC, have probably dipped their toes a little too often in the grim and gritty end of the creative pool since the 1980s. Comic books shouldn’t necessarily lead you to drink after you read them. However, that doesn’t mean gritty stories don’t have value. If you’re going to go with dark and gloomy, might as well go with the best. DC and Marvel cornered that particular shelf space in the 1980s with The Killing Joke and Kraven’s Last Hunt.

Alan Moore has already made the list with Watchmen, but The Killing Joke is another celebrated story where the master storyteller gives us a definitive look at DC’s perpetually morose Dark Knight. Along with artists Brian Bolland, Moore delivers perhaps the definitive Dark-Dark Knight story, and possibly the best Joker story ever written in this prestige format one-shot. The story follows the Joker as he and Batman do their familiar dance after the clown prince of crime escapes Arkham Asylum yet again (seriously, what’s wrong with that place?). Moore probably wasn’t the first to come explore the notion that Batman and Joker are perhaps two sides of the same shadowy coin, but I don’t think there’s any denying he did it best. And he explores it with aplomb. I am always struck at just how creepy and sadistic Moore makes Joker. Scene after scene, especially in the tragic origin flashbacks, the Joker chews up rich page space with his manic insanity. Of course, what Joker does to Barbara Gordon is just as shocking when I read it now as it was when I first read the story twenty-plus years ago. It’s dark, but it works extremely well. The ambiguous ending only adds extra weight to the overall story.

Just a few months before The Killing Joke was released in early 1988, Marvel published J.M. Demattias and Mike Zeck’s six-part story Kraven’s Last Hunt throughout its three Spider-Man titles (Amazing, Spectacular, and Web of, in case you have forgotten). Kraven’s Last Hunt is poetic in its urgency, telling the story of a maddened Kraven who is obsessed with capturing and killing Spider-Man as a final act. His every previous effort has failed, but he knows he can do it. What follows is a grim story about the rise and fall of one of Spider-Man’s greatest foes. The human element is present as well, as Mary Jane Parker, newlywed, struggles to deal with the disappearance of Spider-Man. Moore might be considered the master of comic book storytelling, but I would stand up DeMattias’s script for Kraven’s Last Hunt against almost anything Moore has written, and I’m the resident Alan Moore nut around the NoE Hall of Justice! DeMattias does his level best to make you feel every ounce of anguish Peter, Kraven, and MJ have in this story. It’s not an easy read, but it is one that many readers find themselves coming back to time and time again.

Dark Knight Returns & Days of Future Past

Comic books love to give a “What if?” investigation into the future. Heck, Marvel famously had that exact title running for years and DC had a whole line of books titled Elseworlds devoted to exploring that very concept, where they exclusively made alternate takes on classic stories where things didn’t go the way one might have remembered from the glory days. Comic books especially love to explore the dystopian future where everything goes to Hades. The two best examples of classic comic book trope came in the 1980s from the Big Two. Each are a perfect complement to one another.

In 1986, DC released the four-issue miniseries Dark Knight Returns from Frank Miller and Klaus Johnson. This series took place in a dystopian 1980s where an aging fifty-something Bruce Wayne had retired from being Batman ten years earlier. Of course, retirement doesn’t quite suit Batman, especially with the rise of a gang calling itself The Mutants. Two Face and Joker naturally join in on the chaotic fun, and the series even features an amazing standoff between Batman and Superman, who is now a government shill. It’s a dark and atmospheric tale to be sure, but it’s also an insanely fun reading experience. Miller’s story would set off a nearly three-decade race to see who can bring Batman to his darkest point. If The Killing Joke was the definitive Joker/Batman story, Dark Knights Returns serves as the story that set the tone for nearly every Batman run since its publication. There have been two direct, and woefully abysmal, sequels in recent years because comic books are also about mining nostalgia for serious cash money these days, but those weaker links don’t break the chain of awesomeness of the original.

But five years before Dark Knight Returns, Marvel produced the definitive dystopian story with The Uncanny X-Men’s two-issue story Days of Future Past. This story has all the dystopian/post-apocalyptic elements that any fan could ever want. Mutant and superhero genocide! Internment camps! Nuclear holocaust! Psychic time travel! In just two measly issues, Chris Claremont, John Byrne, and Terry Austin deliver what many readers consider to be the finest X-Men story ever. Let me set the stage for you: it’s the far away year of 2013 and Kitty Pryde’s mind is sent backwards in time to stop the events that led to such an awful future. What follows is a desperate attempt on the part of future Kitty to stop the awful future of 2013 from happening. Too bad Byrne, the apparent architect of the story, couldn’t save us from today. Like The Dark Knight Returns, Days of Future Past spawned several less than stellar sequels, but the original remains a potent example of this classic comic book allegory.

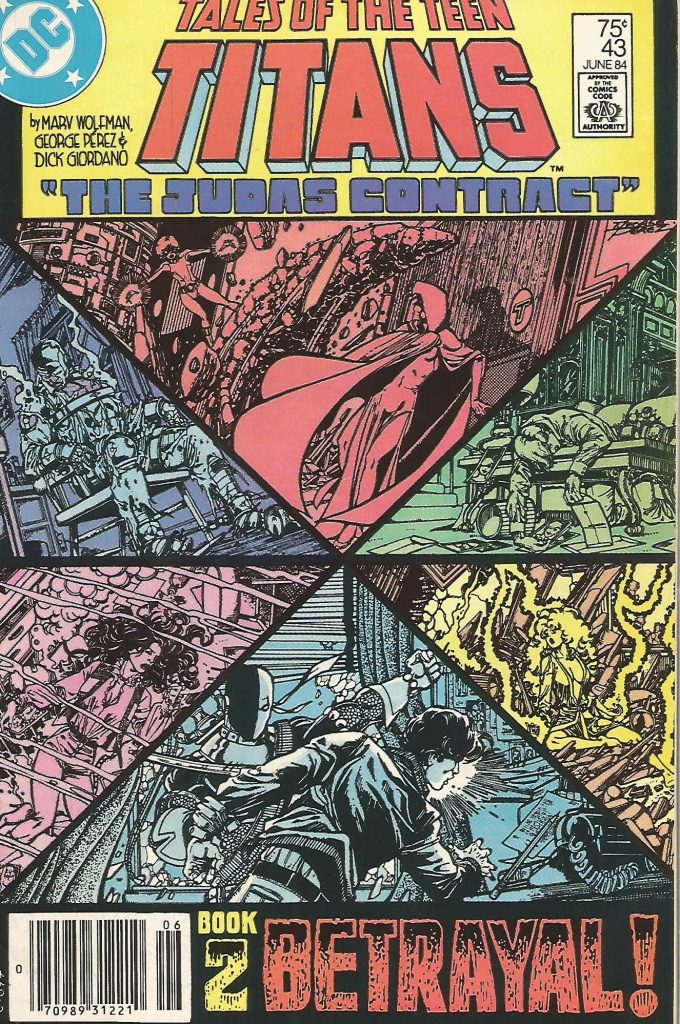

The Judas Contract & The Dark Phoenix Saga

Comic books are awesome. It always surprises me that we fans often forget about just how good we have it when it comes to classic, infinitely re-readable runs. Definitive comic books runs are tricky to nail down for many characters, but to misappropriate Oliver Wendell Holmes, for some series fans know it when they see it. Perhaps no two comparable iconic runs from DC and Marvel are almost as universally beloved by their fanbase as The Judas Contract and The Dark Phoenix Saga.

Marv Wolfman and George Pérez’s New Teen Titans reboot in 1980 gave a fresh coat of paint to the old, less-than-successful Teen Titans series. In fact, these were no teens at all. Wolfman and Pérez had aged the earlier characters like Robin and Beast Boy to early adulthood and introduced a few new Titans like Raven, Cyborg, and Starfire along the way. One could practically label their entire run a classic, but The Judas Contract stands out due to its story of betrayal and loss. At the behest of Titans foe Deathstroke, a young superhero named Terra infiltrates and joins the Titans with one purpose: their destruction! What follows is classic tale of deception, treachery, and loss. No spoilers, but it’s well worth checking out.

While checking out The Judas Contract, why not give another undeniable classic of betrayal a try? Like the New Teen Titans, the X-Men were hardly a team of whizzbang teenagers by the time the The Dark Phoenix Saga rolled around in Uncanny X-Men #129-138. Brought to you by the same team that did Days of Future Past, the The Dark Phoenix Saga features the downfall of original X-Men member Jean Grey. Jean had been possessed by the Phoenix Force way back in Uncanny X-Men #101, during the early days of the all-new, all-different X-Men reboot.

Over the intervening issues/years, her powers grew stronger and more erratic. Eventually, Jean dubs herself Dark Phoenix, kicks the X-men’s collective butts, goes on a space trip, and ends up devouring a star, killing an entire planet. That’s a pretty epic road trip! The Shi’ar put Phoenix on trial and abduct the X-Men, who elect for a trial by combat. That ends about as well as any trial by combat in any form of popular entertainment. Though not a story of outright betrayal, The Dark Phoenix Saga is no less a heart wrenching tale of loss and powers gone mad. The entire first run by Claremont and his collaborators is filled with memorable stories, but few stories rise to this level of pathos.

Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? & God Loves, Man Kills

Comic books often have a hard time putting a definitive “the end” at the conclusion of any story. That’s not the nature of the beast. These characters are meant to go on and on, to endure even the harshest of circumstances. Comic fans have long understood that radical changes to the status quo are typically short, seldom outlasting the creative team that tried to shake things up in the first place. It’s a rare opportunity for tentpole properties from Marvel and DC to reach any true conclusion. However, there are rare circumstances that allow creators to give a final word on a character or team.

With Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?, Alan Moore and legendary Superman artist Kurt Swan, in what turned out to be his last Superman work, were given such a chance to literally create an ending for the Superman saga in 1986. The impending reset that was Crisis on Infinite Earths not only provided John Byrne with the opportunity to redefine Superman for a new era, it also provided Alan Moore with the opportunity to write the last official pre-Crisis story for DC’s flagship character in Superman #423 and Action Comics #583. Editor Julius Schwartz treated his last two issues before the reboot as true final issues. Moore approached the project as a way to provide a homage to Superman, rather than going with a gritty “death of Superman” angle. Despite there being some impactful deaths, the whole darn thing is fairly positive and upbeat. I know that sounds surprising given Moore’s reputation, but his two issue send off for Superman reads like a love letter to the character and his supporting cast. Moore lovingly and faithfully traces out the final years of Superman. It’s a surprisingly sweet send off for a great character.

X-Men: God Loves, Man Kills isn’t quite a “last story” in the way Moore’s Whatever Happened… is for Superman, but I have always read it as such. Published in 1982, God Loves, Man Kills is an original graphic novel by Chris Claremont and artist Brent Anderson. The graphic novel was format specifically used for this story as it was intended to be an X-Men tale set outside of the main continuity of the regular Marvel Universe. Because the story was considered to be outside of continuity, it gave Claremont the freedom to push the boundaries of his storytelling in ways that working of the main Uncanny title would not allow. The story follows O.G. mutant terrorist Magneto investigating the murder of two mutant children by the followers of a radical anti-mutant preacher William Stryker. Professor Xavier is eventually kidnapped by Stryker, and the X-Men are forced to join with Magneto to save him. The story mixes in themes of racism and violent extremism, which is as pertinent today as it was in the early 1980s. Though it was retroactively squeezed into continuity with the main Marvel Universe in the early 2000s, I much prefer to think that God Loves, Man Kills still stands alone as a standalone X-Men tale that gives us an ambiguous but satisfying alternative ending to the X-Men saga.