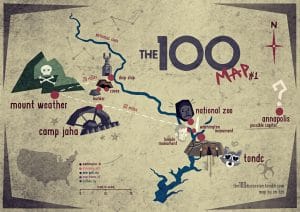

The 100 used to be one of my guilty pleasures (this is true for Morgan as well). After a episode a couple years ago, I grabbed my iPad for a search of what maps might illustrate the world of The 100. I was also looking for a systemized catalogue of characters, locations, equipment, and groups. Really, I wanted The 100 RPG sourcebook, but all I got was a weak-sauce Wiki.

Worldbuilding is creating fascinating worlds that readers, viewer, and players want to come back to again and again. Worldbuilding is outlining locations, characters, and conflict to serve as a tinderbox for storytelling potential.

I’m sure I’m not the only person who when first picking up a fantasy or sci-fi book looks first to see if there is a map just inside the cover. Worldbuilding is important; worldbuilding is engaging.

But just how detailed does a created world need to be?

Both God and Tour Guide: The World of The 100

What’s the actual answer to where the Ice Nation resides relative to Trikru or Skaikru in The 100? Well, the actual answer is that is doesn’t matter until the story dictates it. Like any evocative treasure map, it’s a simple unlabeled X that won’t get a name until it needs one.

What’s the actual answer to where the Ice Nation resides relative to Trikru or Skaikru in The 100? Well, the actual answer is that is doesn’t matter until the story dictates it. Like any evocative treasure map, it’s a simple unlabeled X that won’t get a name until it needs one.

But do the writers of The 100 draw a map of their world on a whiteboard in the writer’s room? I’m sure they do. After all, they’ll need notes and an outline for plotting considerations. Plus, it’s materially significant to their location scouts.

So why haven’t they published The 100 Sourcebook or the Encyclopedia of The 100? Frankly, they will. After all, they can make money on it. But for now they don’t have to. Because the writers of The 100 (and whatever media property we want to substitute in here) play two roles: God and Tour Guide.

The World of The 100: Playing God; Being Tour Guide

The writers of The 100 are its creator. I’m not invoking the name of Yahweh, I’m just saying they are the ones who create the locations and characters that inhabit the fictional world. And at the end of a hard day of writing you want to be able to put down your pencil and declare ‘And it was good.’

The writers of The 100 are its creator. I’m not invoking the name of Yahweh, I’m just saying they are the ones who create the locations and characters that inhabit the fictional world. And at the end of a hard day of writing you want to be able to put down your pencil and declare ‘And it was good.’

So you don’t want your viewers to see the seams of the world you built. You don’t want to be sloppy, in other words. Create order. Outline. Develop rules.

Attempt to make the universe you’re creating sound. Set up rules for the universe, then follow them as a writer. If you are in a frigid habitat, then the characters should be wearing fur. Language and dialogue should be plausible. Behaviors should make sense based upon surroundings. You get the idea.

What this doesn’t mean, however, is that once you’ve made up the rules for the universe, you necessarily have to have an answer for every single question that might come up later. If you’ve built the universe soundly, when previously unanswered questions come up, you can create plausible answers based on the rules of the world you’ve built.

Or when a nerd like me is looking for a map, worldbuilders can say “Look for our exciting Visual Dictionary of The 100, coming soon for $29.99 wherever fine books are sold!”

Or when a nerd like me is looking for a map, worldbuilders can say “Look for our exciting Visual Dictionary of The 100, coming soon for $29.99 wherever fine books are sold!”

Until then, move the viewers along quickly enough that they don’t see the seams. Be a tour guide, letting them see only what you are ready for them to see. Worldbuilding isn’t about so thoroughly developing a world that as creator god you need to have an immediate answer for every possible consequence of the development of your universe.

Worldbuilding often needs to only go for sufficiency — that the world is logical enough to play in for the purposes of your immediate story — and direction — moving people along in the story quickly enough that they don’t have time or the interest to question your worldbuilding or story-telling choices, at least until the story is done and you’ve pushed them back out into the real world, waving and smiling.

The World of The 100: Lessons Learned

So what are our worldbuilding lessons learned that are true for The 100 or your homebrew D&D campaign?

So what are our worldbuilding lessons learned that are true for The 100 or your homebrew D&D campaign?

Be creative. Play god, creative interesting and fascinating characters and locales.

Set rules. Outline and create a system. Don’t be sloppy, be sound.

Let people see only what they are ready to see. It’s OK to have an unlabeled mountain range just over yonder. If they ask about it, let them know it will be revealed all in good time.

Worldbuilders are an interesting combination of god and tour guide. They create worlds, but then only let readers or viewers see the parts of the worlds that tell the story they want to tell. What that means is sometimes there are parts to the world that the writer hasn’t seen either! But sooner or later, we’ll all get our map.