I’ve never been shy about how much I love Brian K. Vaughan’s comics. I’m a fan of pretty much everything he’s done, from Runaways to Ex Machina to Y: The Last Man to Saga to Paper Girls. So any time he puts out a new project, my heart beats a little faster. So it was a few years ago, first with the future noir Private Eye and then with We Stand On Guard, his Canada vs. America “military thriller” with Steven Skroce.

I enjoyed them both, but there was something…off about them. They didn’t seem quite right. Neither one seemed like they really fit with what was going on. Re-reading them both recently, I figured it out: Neither is a product of their time. One was written a few years too early; the other, 14 years too late.

A Tale of Two Brians: We Stand On Guard and Private Eye![]()

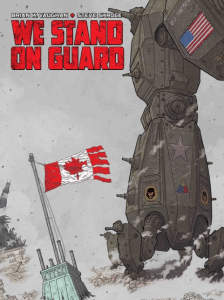

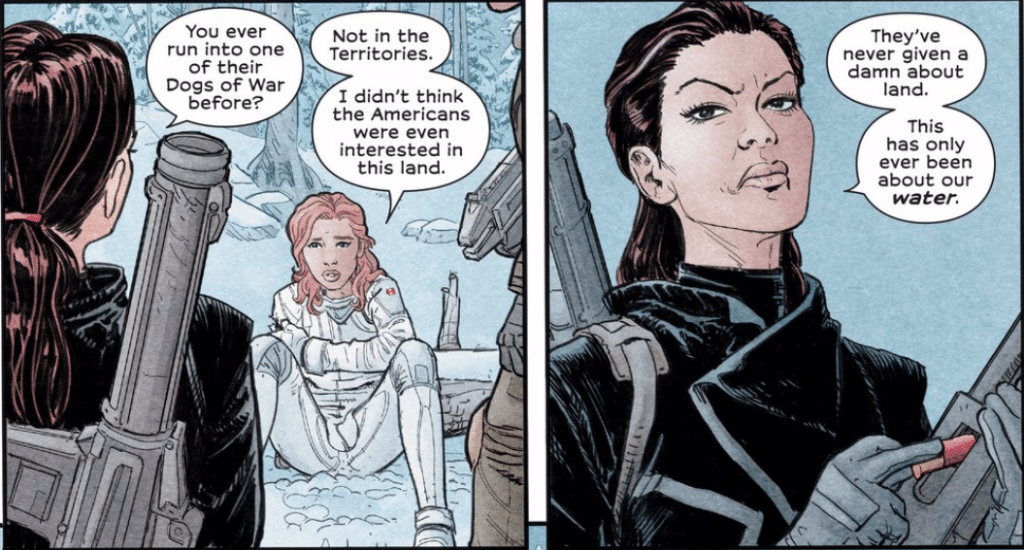

I wrote about We Stand On Guard, Vaughan’s unsubtle Iraq War allegory, before, but in case you missed it, here’s the pitch: It’s the early 22nd century. Believing Canada responsible for a major terrorist attack, the United States invades its northern neighbor. There are questions about the truth of the attack and the motivation behind the invasion. Canadian insurgents fight a guerrilla war against the occupying Americans.

We don’t like to get political here at Nerds On Earth (well, my bosses don’t–I have, on occasion, dipped my toes in the waters), and a debate on the merits of the war in Iraq is indisputably outside of our wheelhouse, so I’ll leave that aside. What isn’t up for debate is the shift in the cultural opinion surrounding the war, and that the now broadly-accepted consensus is that it was a Bad Idea.

If Vaughan had written We Stand On Guard in 2004, it would have destroyed his career–but he’d have been vindicated by history, and we’d look back on him now as one of the most subversive and forward-thinking writers of the 21st century (just like Sylvester Stallone–ask me later). As it is, We Stand On Guard seems like an unnecessary statement–like somebody walking out into the middle of the street and declaring, “This might be controversial, but I don’t think we should hang people for witchcraft!” It’s like, congratulations, I guess, but you aren’t putting a lot on the line, here.

That wasn’t the case back in ’02-’03. Then, anyone who questioned our decision to put boots on the ground was pilloried for lacking sufficient patriotic faculties. If he had said, in 2003, that we were unjustly subjugating a sovereign nation solely for natural resources, we’d have roundly criticized him as a bleeding-heart lefty. If, in 2003, he had portrayed the American military establishment as corrupt torturers, we’d have howled that he wasn’t supporting the troops. If, in 2003, he wrote a comic where the heroes were the plucky resistance standing up against a malevolent, technologically-superior force, we’d have let that one slide–that’s literally the plot of every good Star Wars movie, so that’s okay. But to have the bad guys be Americans? We’d have buried him so deep he’d still be digging his way out.

That’s not to say it’s bad by any means. I think there are a lot of questions we still need to answer about America’s experiment over in the Middle East, and this comic does an admirable job of asking them. But there just doesn’t seem to be as much need for We Stand On Guard as there was, say, ten years ago.

That’s not the case for Private Eye.

Private Eye Browsing

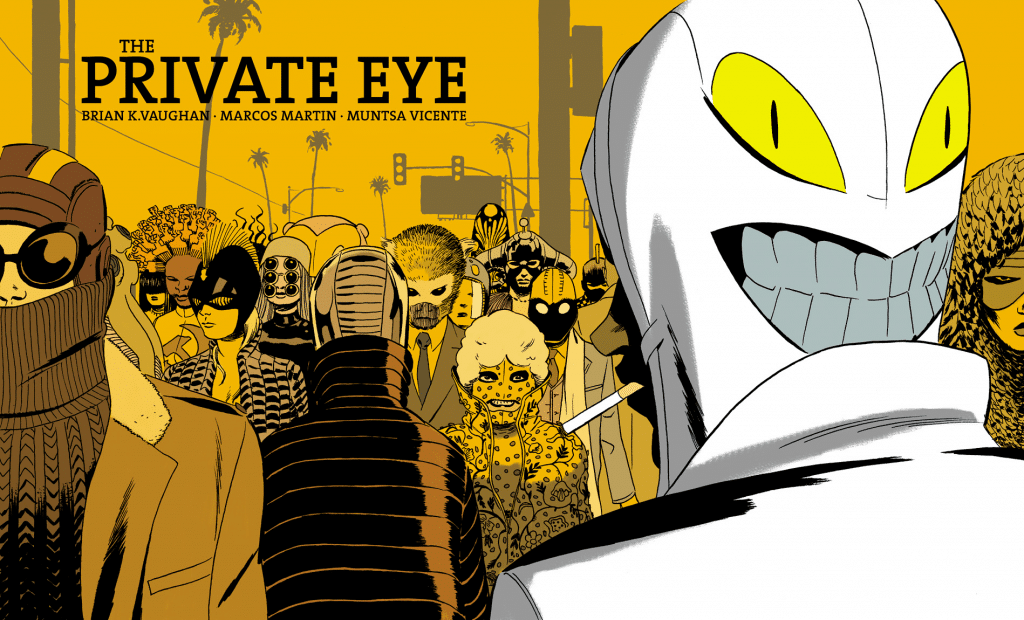

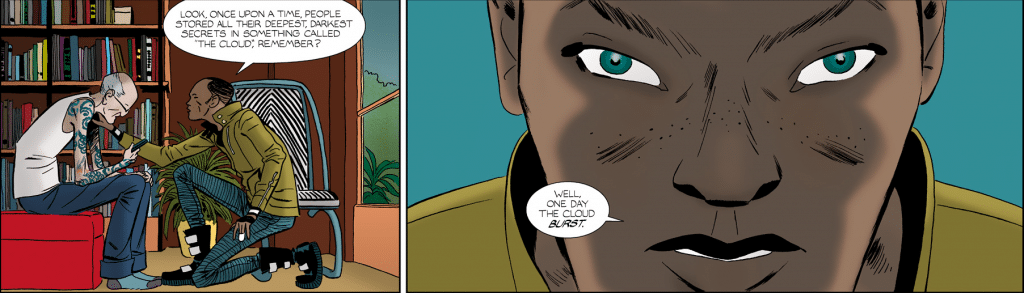

If We Stand On Guard was too late, then Private Eye, released on the Panel Syndicate pay-what-you-want platform and featuring art by Marcos Martin, was a little too early. In 2015, a comic about the limits of privacy and the brittle fragility of our online identities was certainly relevant–I mean, I haven’t gone online without a VPN connection in years–but it was hardly on the forefront of the national conversation. Now, with half a billion Yahoo! accounts stolen, with emails from the DNC published for all the world the read, with Congress opting to give ISPs control over your personal information, it seems like even the tech-illiterate stodgy formal press is giving this subject a bit more attention.

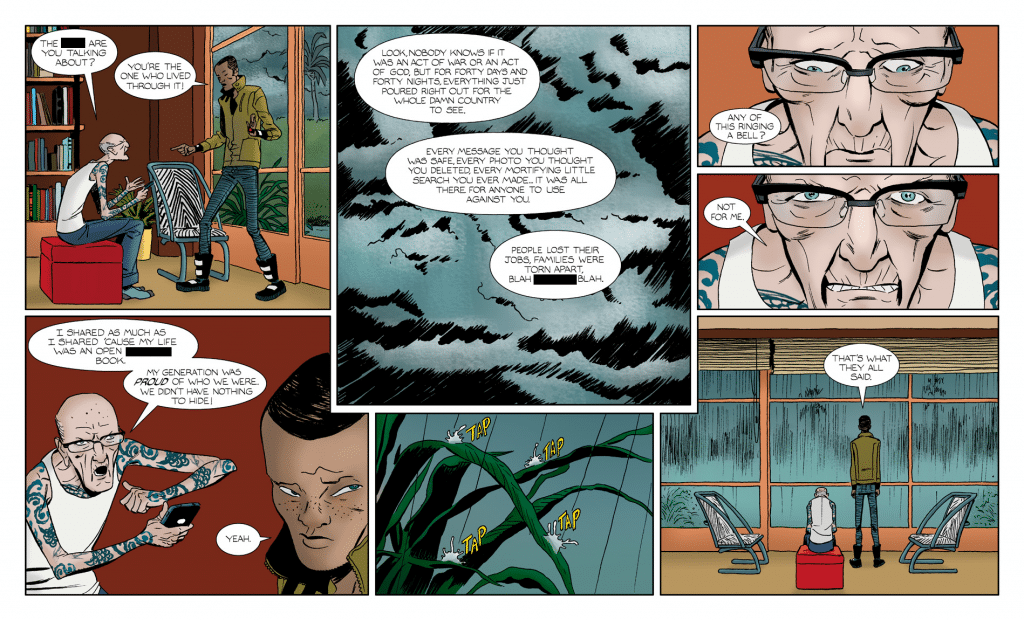

Private Eye is a detective story with a lot of puns and clever sight gags, but really it’s about privacy. It’s set on the eve of America’s tricentennial, and everything seems a little anachronistic–no cell phones, no digital cameras, music on vinyl. Oh, and everybody wears masks. Why? Well, I’ll let our hero explain:

In Private Eye, Vaughan explores a world without connectivity, where we can carry our online anonymity into the real world, where privacy is valued so highly that the press doesn’t report on the news, it keeps it from getting reported. The entire work is an exploration of how we allowed our secret lives to get out of hand, and the lengths we’d be willing to go to in order to preserve them. The focus of Private Eye is right there in the title.

In a world of Edward Snowden and Wikileaks, there doesn’t seem to be anything more important to the future of the internet than privacy. Right now, we’re caught in the middle–we share as much as we can on Facebook and Twitter but we fear the contents of our searches becoming public knowledge. In Private Eye, Vaughan imagines one possible extreme, one where the risks of exposure are so great, people go back to using phone booths.

Is Brian K. Vaughan Displaced In Time?

I think the easiest explanation for these two comics is that Mr. Vaughan is unstuck in time. He’s having trouble remembering when he is, or what controversy he’s trying to be angry about. Sometimes he’s living in the early Aughts, when “Hey Ya!” is blasting on every first generation iPod. Sometimes it’s closer to 2020, when unspeakable horrors are crawling out of the cellular networks. He tries his best to be topical, but he keeps missing the mark.

At least he makes great comics when he does it, though.

Ross Hardy wrote a comic book you can read here, a book book you can read here, and blogs about politics here. Follow him on Twitter here.