It’s the dog days of summer. We’re in the dead zone of nerd media, caught in the Bermuda triangle of August. Comic-Con has come and gone; E3 is just a memory; as is GenCon. We’re months from the big fall videogame and movie releases. TV networks are scraping the bottom of the barrel and burning through game shows and one-shot ideas. Even sports are in a lull—baseball teams are caught in late season pushes for the playoffs, the return of college football is a week away, and the return of NBA ball is a distant mirage on the horizon.

With nothing much going on at the current moment, let’s turn back the pages to the middle chapter of one of the best movie trilogies ever made: 1984’s Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. We’ll start this two-parter with a look at the difficulties of making the film, and finish with a look at its place in the internal mythology, and greater story, of Dr. Henry Jones, Jr.

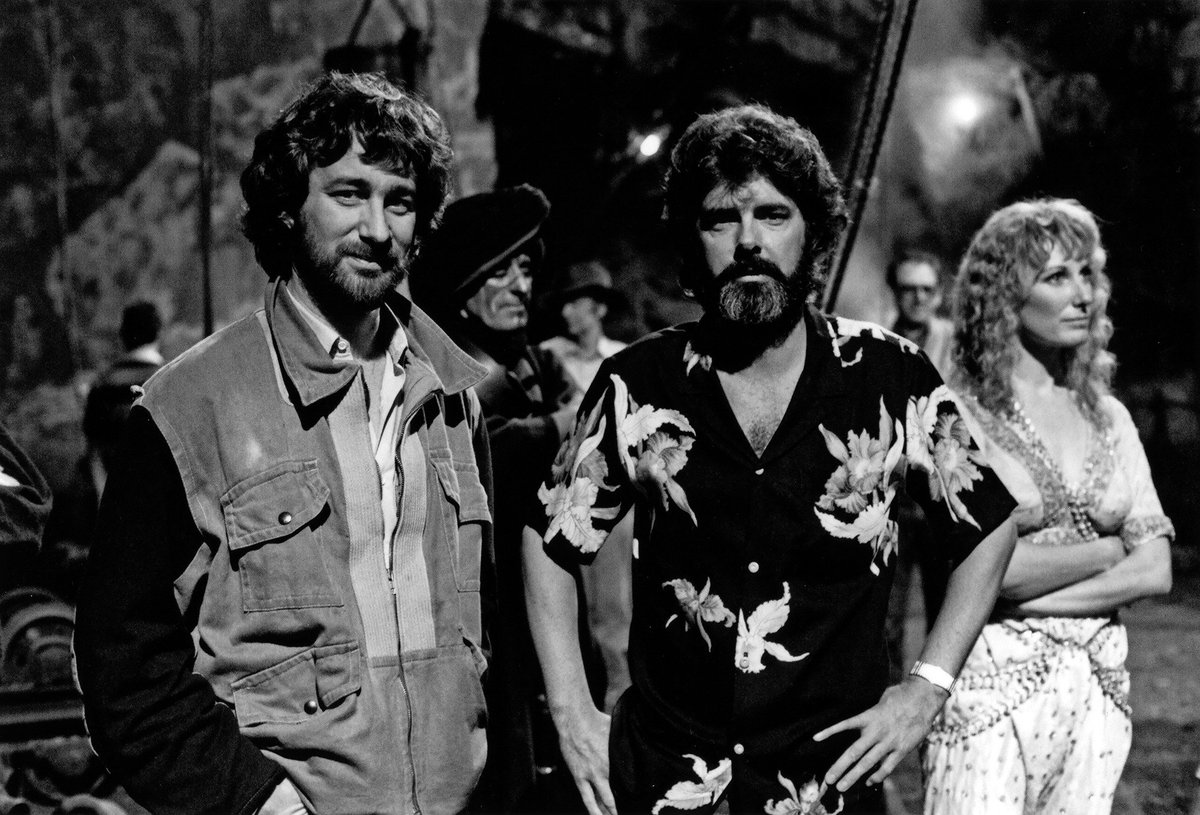

In the early to mid 1980s, Steven Spielberg and George Lucas were, bar none, the most famous and respected creators in the movie industry. They had both produced cutting edge films for over a decade, balancing blistering special effects with sublime acting from great (and sometimes unheralded) performers and timeless soundtracks courtesy of the legendary John Williams.

They teamed up for the first time on 1981’s Raiders of the Lost Ark. An intoxicating blend of action, humor, a killer soundtrack, and a deep affection for old-fashioned adventure serials, the film left the world eager for more adventures with Dr. Jones. Production on another Indy film began between and in the midst of several other films (Return of the Jedi, ET, Body Heat, Poltergeist).

The production was plagued by unexpected obstacles. Lucas’ pre-Raiders promise to Spielberg of three prepared Jones stories turned out to be false, so a treatment, complete with plot and script, had to be made from scratch. Various locations were proposed for filming (Scotland for a ghost-based story, the Great Wall of China for a lost world of dinosaurs) as Lucas cast about for plot ideas. It’s worth noting that the more supernatural elements of 2008’s oft-derided Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull fit in with some of Lucas and Spielberg’s brainstorming for the films during the 1980s.

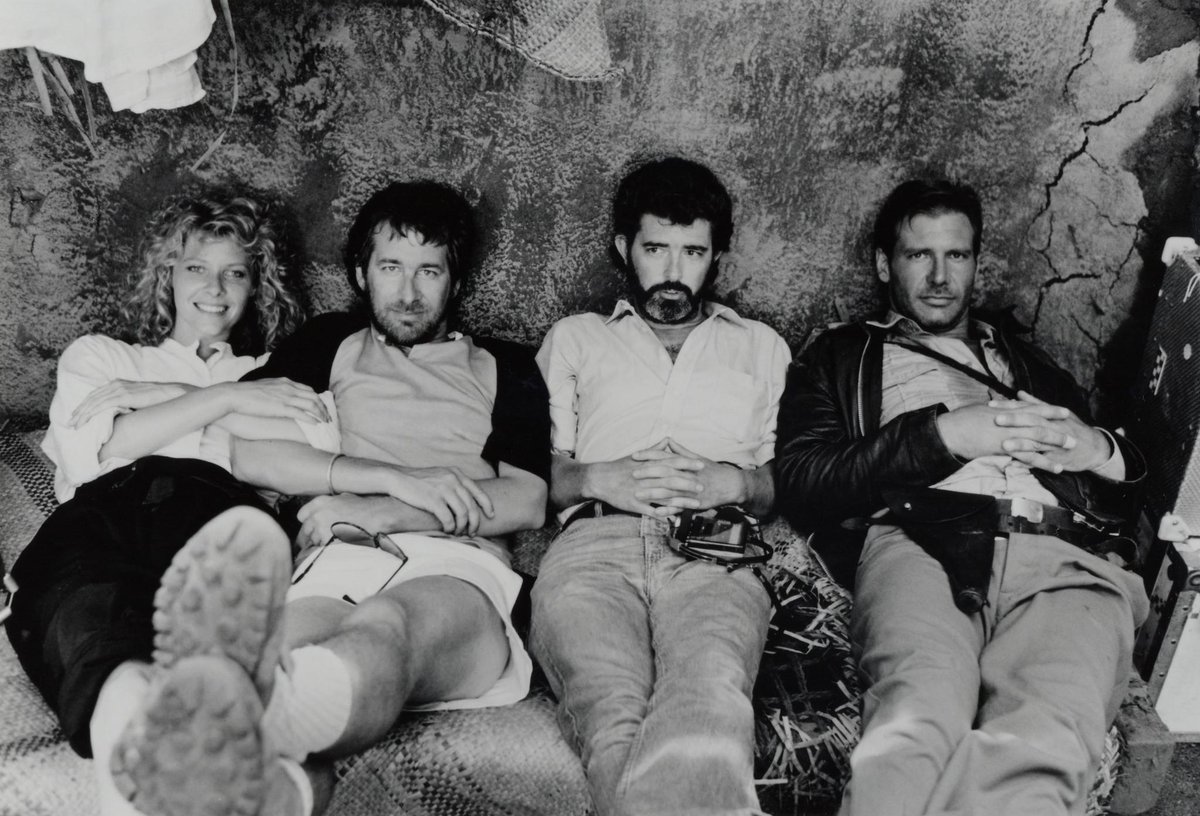

More personal issues erupted during production. Both Spielberg and Lucas were going through romantic breakups, to which both have partly attributed the darker, more pessimistic tone of the film. Lucas would remember in 2008, “It ended up darker than we thought it would be. Once we got out of our bad moods, which went on for a year or two, we kind of looked at it and went, ‘Mmmmm, we certainly took it to the extreme.’”

After a story was decided upon—Indy would seek fame and glory in China and India, searching for the mythical Sankara stones and taking on the murderous Thuggee cult—the business of shooting the film could begin.

The shoot proved difficult. Despite being set in northern India, the Indian government found the script so offensive that they refused to let Spielberg shoot on location, forcing the film’s Indian sections to be filmed in Sri Lanka or on soundstages. An elephant ate part of the red dress worn by Kate Capshaw, requiring extensive repairs to a costume piece already made of beads produced during the 1920s.

Major thanks to J. W. Rinzler’s excellent The Complete Making of Indiana Jones for many of these behind-the-scenes tidbits. His book is incredible, and filled with so much movie magic that you’ll sparkle by the last page.

Harrison Ford, performing most of his own stunts as was his habit, suffered a severe herniated disc in his back during the bedroom fight scene (look for the somersault). Ford fought through the pain, laying in a hospital cot between takes to ease his agony, before finally agreeing to undergo surgery. He was out for a month and a half, basically shutting down production until he could safely return.

What would the final product look like? How would the public and critics respond to Temple of Doom? Could the difficulties of production pay off, financially or creatively? Come back to see how the film would change our concept of the daring Dr. Jones!