I rolled my first d20s exploring the very earliest D&D dungeons. You know, the wonderful stuff that Gary Gygax was creating in the 70s and early 80s, adventures that are being revitalized in the Dungeon Crawl Classics by Goodman Games. These OG dungeons were nothing more than mazes that made little architectural sense and were designed to confuse and befuddle players to get them lost and put dangerous creatures in their path.

Some of them, like Tomb of Horrors, were literally designed to be a meat-grinders that punished players and no amount of 10 foot poles could get players around the traps. White Plume Mountain was pure wizardry silliness. Others, like Expedition to the Barrier Peaks were similarly maze-like but the goofy, magical nature of them was hand-waved through the pretense of alien technology.

MT Black described the encounters of these old school classic dungeons on Twitter like this: “In the same way, encounters within the dungeon were decidedly “gonzo.” The emphasis was on the weird and wild, rather than creating a cohesive ecosystem. Imagination was king and verisimilitude was not really in the design dictionary.“

Remember, some of the D&D mechanisms that we take for granted nowadays hadn’t even been invented yet, so not only were the dungeons maze-like and the encounters gonzo and disjointed, but the gameplay of the encounters was fundamentally different as well. For example, I mentioned the 10 foot pole.

Players wandered about, poking things with the 10′ pole because skill checks hadn’t been invented. Since rolling a d20 to check for traps hadn’t been iterated at that time, players found traps by triggering them and triggering it with a 10′ pole hopefully kept them far enough out of harm’s way. [More on exploration with a 10′ pole here.]

So, even play styles within individual encounters was different. And encounters in no way seemed to flow together room-to-room. There was no overarching story in these original dungeons, but that was something that Gygax quickly addressed.

Keep on the Borderlands was an early Gygax adventure that focused on exploration via a hex map. And while it is true that Keep didn’t have a strong central storyline, it was the precursor to what we now call “sandbox” adventures and challenged players to write the story themselves. In short, while a detailed story wasn’t drafted beforehand, the story unfolded organically as the players explored.

But shortly thereafter, the magical mazes of early D&D were about to receive a major innovation in the early 80s and let’s again credit MT Black for this observation: “This all changed in the 1980s. Old school grognards even have a date for this change – 1982 when Tracy & Laura Hickman published I3 Pharoah. A few quiet corners of the net even call this the “Hickman Revolution”.

The emphasis now was on an overarching, cohesive plot, usually with epic overtones. Dungeons were not silly little mazes, but structures that made sense architecturally. And encounters had to make sense within the overall plot. This style of play was enormously popular.” It was a critical innovation of the time.

There was a new emphasis on realism and verisimilitude. Gone was the gonzo. Gone were the silly encounters and silly mazes. The story became more baked and a layer of thoughtfulness was woven throughout the adventure that attempted to provide an rationale for players advancing from encounter-to-encounter, while also providing a rationale for encounters that had an anchor in realism.

D&D had its roots in historical wargaming, which were played with miniatures on tabletops, using sophisticated rules. The “story” in those games was the historical battle that was being simulated. So D&D played up the “tabletop” aspect via the tactical use of miniatures being moved around on a grid. It also played up the “game” aspect by introducing copious rules to adjudicate actions using dice rolls.

While a wholly imaginative game of fantasy, very little was fully left to the imagination, as there was a rule for it. Whereas nowadays, tabletop roleplaying games play up the “roleplaying” aspect. Players can oft be professional voice actors or even work in the entertainment industry, having a professional background in screenplay writing.

By comparison, this entire storytelling aspect was in a nascent state, having literally just been invented by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson. But even Gary Gygax – the very man who put the “roleplaying” into wargaming – famously snarked that if roleplaying was all he wanted to do, he’d “join a high school drama club.”

The fantasy was expressed I the gonzo nature of the adventures and that was a feature, not a bug. Yet in just a few short years Gygax himself – then certainly Tracy & Laura Hickman – began to iterate. Pharaoh then later Ravenloft had characterization at a level not previously seen in an adventure product.

While in the early days of D&D, the story of an adventure might simply be that you’ve stumbled upon a cellar door, an adventure doesn’t require much more than a few connected rooms scribbled on a piece of graph paper. The “story” was to get down there and kill some monsters to take their loot, which is not the kind of thing you roleplay, you know?

But the Hickmans introduced villains and NPCs that dripped with personality and placed adventurers in situations where you couldn’t help but want to interact with them.

The architecture of locations was iterated as well. Gone was the madcap wizard lair that was more a funhouse than a logical lair. Instead, a layer of plausibility was added to the fictional worlds and they began to pursue logic – not magic – as the glue that held it together.

Whereas older dungeons might have a room with a bugbear, a room with a zombie, then a NPC in the next, and writers wouldn’t even spare a thought for how those creatures co-existed, much less why they were down there in the first place.

But if you are alive, you eat. So newer dungeons take care to place a stack of provisions in the corner if there is a group of pirates living there, for example. They’ll have a water source. (So if a clever adventuring party wants to poison the watering hole to soften up the enemy? Well, give them some XP.) Even more, the story will often give purpose to why the creatures were in the dungeon in the first place.

Oh, and maybe map makers remembered to account for where monsters might go to the bathroom.

But what was lost?

While the Hickmans were talented enough to combine the best aspects of the “old school” approach with a new-found emphasis on “realism,” many others failed. And failure often meant a boring adventure.

In fact, many adventures became decidedly “mundane.” While they strived for more realism they sometimes forgot the fantastic. There’s no giant crab in boiling water like in White Plume Mountain because that doesn’t make any logical sense.

Again, MT Black: “Dungeon architecture became more straightforward – because that makes sense – but also more tedious. When my friend said he found dungeons crawls dull, the fault was not with him and his group. It is because modern dungeons often are dull.”

Last year I was messaging with famed Dungeon Magazine writer Willie Walsh and I thanked him for the sense of humor he brought to adventure writing. Willie was famous for his old school funhouse Wizard towers, but we can’t turn back the clock to those times.

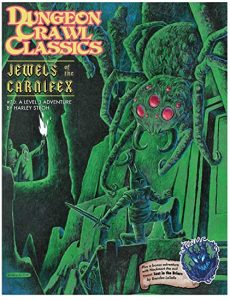

Modern audiences want a sense of verisimilitude or bust. Even the Dungeon Crawl Classics books are updated to apply a sense of story and logic when possible.

But let’s never forget that these are games, not simulations like the wargames of yesteryear that Gary Gygax used for inspiration. The irony is Gygax and Arneson created D&D to loosen up the exacting demand of verisimilitude and in doing so, let loose with the adventure.

It took the Hickmans and many others to help D&D fully realize that dream by injecting the story and roleplaying that the game became known for.

But let’s not forget to inject “the fantastic” into our dungeons like a Mountain Dew Code Red into our veins. After all, who cares where the Wizard goes to the bathroom? They can cast prestidigitation.